It has been a big week in healthcare news. One cannot have missed all the talk about Kevin Rudd's bold new plan, to take health care where health care has never been before (except in Victoria). Much of these reforms derive from the

previously published NHHRC report which I will not expand upon. I will, however, give some of my mind on efficiency in the medical sector.

Nicola Roxon loves banging on about efficiency, and funding the "efficient costs" of health care. Here she is on

ABC's Lateline on the 27th of July last year:

NICOLA ROXON: Yes. Yeah, that's right. They - of the funding, what they recommend - and remember we're talking about their proposals to us - is 40 per cent of efficient funding, which is actually an interesting concept, which is the states should fund the extra 60 per cent and any inefficiencies that are in their system. And they even say if you even went up to 100 per cent in the future, you should only pay 100 per cent of an efficient system, which would sort of have a penalty there for -

TONY JONES: Just to clear up what that means. Effectively, that means that, centrally, you would set the actual cost that should be charged for individual operations. A hip replacement, for example, should cost X and that would be the efficient cost.

NICOLA ROXON: That's right. Yep. That's right.

TONY JONES: Inefficient costs would be anything above X, is that right?

NICOLA ROXON: That's right. And so you would have a activity-based and efficiency-based payment. So if hospitals were - in particular states were not good at particular procedures, they would bear the extra cost, or if you're in a booming state where you've got a higher population putting more demand on your hospital services, you get paid more because you're undertaking more activity. That's the key tool that they are recommending we use for funding, which is a big change from where

we are in block funding the states for their whole activities.

Nicola Roxon - ABC Lateline - July 27 2009

There is plenty in the media about the pros and cons of a central pricing authority, and either additional or streamlined bureaucracy (depending on your point of view), but I am more interested in the "efficiency" concept. Now, efficiency in health care can be measured in very different ways, but generally they do not directly relate to improved health care, quality of life, or prolonged life expectancy. Efficiency does not automatically lead to improved population health.

The usual argument is that if you treat more patients with the same amount of money, then you are benefiting more people and therefore improving the health of your population. That is great if you have lots of waste and slack in your system but that is a very managerial and administrative view of the world. There is, of course, a great deal of waste and slack in our health system nationwide partly because health events are by their nature episodic and unpredictable (just look at the recent swine flu pandemic) and health infrastructure is not something that can be ramped up and down as necessary.

An analogous situation would be that your would not want all fire stations to be working at full capacity all the time, because when a particularly nasty factory blaze occurred there would be nobody to fight it. There is therefore an inherent downside at encouraging hospitals to work at > 90% bed capacity.

Unfortunately the usual measure of efficiency is throughput, which features very highly in health-administration KPIs (also known as "Key Performance Indicators"). For example, a standard means of measuring emergency department efficiency is how many patients are treated in a day, or a month or a year. Similarly we often ask how many patients are seen in a clinic, how many patients are admitted or discharged from hospital, how many operations performed in a month, patients taken off a waiting list, etc.

Obviously these are very simplistic views of the world and so token attempts are made to complicate things by "weighting", or "prioritising", or adding "descriptors" - all managerial jargon-speak for abstracting these figures from real life. The reason these KPIs predominate are:

- They are readily reproducible (there is a defined common method for calculating these KPIs)

- They are readily manipulated (there is no point monitoring a KPI unless you can improve it... ostensibly by improving performance, but in reality by a short term funding boost, or changing the way it is calculated)

- They are readily manipulated in the short term (there is no point monitoring a KPI that takes 20 or 30 years to improve upon)

But back to the point I wanted to make. Kevin Rudd's whole health reform is said to be about eliminating State and Federal buckpassing, or the "blame game" as he likes to put it. This is mere political smoke and mirrors for what is the real purpose of these reforms. I am not saying that this is not worthwhile or important reform - but it should be seen for what it is.

The Blame Game

It has always been human nature to seek to blame someone else for your troubles. Currently our public hospital system is composed of infrastructure funding which comes from Federal and State Governments, recurrent operational funding which comes from State Governments (except when Federal Goverments seek short term headlines by giving away more money), and an Aged-Care system which comes from Federal Government funding.

All of these systems are interdependent, and the only thing that is really being changed is that the Federal Government is proposing to pay for recurrent operational funding through these new reforms. This pays for wages and consumables but who will pay for

rebuilding a hospital or adding ICU beds? Who will decide whether a

new hospital should be built or relocated against parochial or local interests? It is only natural that every resident wants to have every subspecialty service at their local and nearest hospital, even when this is a recipe for substandard care or unsustainable funding, and

rural hospitals need to focus on core services and expanded primary care roles (

PDF). Who will make the hard decision to remove maternity, or paediatric, or oncology services from some hospitals and centralise them at another? I'm no expert, but I don't see the Federal Government Reformists putting their hands out - and so the blame game continues.

Furthermore, Victorian Hospitals regularly find ways to manipulate the case-mix funding system to try to squeeze extra money out of the State Government. This is not unethical or immoral - it is just a fact of how the system is designed that a hospital cannot remain viable other than to make the most of the system under which it operates, and if that means improving your funding by meeting the targets in a innovative manner, then that is what the system encourages. Just like Darwinian evolution. Only now, hospitals (and State Governments) will be working hard to find ways to maximise the Federal Government's "Efficient Costs" payments. Get ready for some creative accounting, Kevin!

The Real Reform

The underlying purpose of this reform is no secret - it is merely obscured and obfuscated by the "Blame Game" argument. Kevin Rudd himself has said in his

Australia Day Speech:

Treasury analysis which will be contained in the Government's upcoming Australia 2050 report points to the fact that over the next 40 years real health spending on those aged 65 and older is expected to increase around seven-fold. Real health spending on those aged 85 and over is expected to increase 12 fold.

This is a product of the increasing age of Australians overall and secondly the fact that within innovations in pharmaceuticals and medical technologies and the rest the cost of treating each individual aged Australian will rise as well. That is our first problem.

The second problem is, of course, the proportion of Australians in the workforce generating the tax revenue to support those services will become less.

So what does Australia, in response to this 2050 report that we will release soon, do about the challenges for the future when it comes to this ageing of our population.

One further thought we should bear in mind is the impact on our budgets.

Forty years ago, Australian Government spending on health equated to 1.2 per cent of Gross Domestic Product.

In 2010, Australian Government health spending equates to 4 per cent of GDP, and the Intergenerational Report projects that it will rise to 7.1 per cent in 2050.

In dollar terms, that's an increase of over $200 billion by 2050 - and equates to an increase in average Australian Government health spending per person in real terms from $2,290 today to $7,210 in 2050.

These are figures we should all reflect on.

Rising health and hospitals spending is already having an impact on state budgets.

States and territories have experienced growth in health spending of around 11 per cent per year over the past five years.

This contrasts with growth in state revenues of around 3 to 4 per cent a year.

Rapidly rising health costs create a real risk, absent major policy change, as state governments will be overwhelmed by their rising health spending obligations.

If current spending and revenue trends continue, Treasury projects that the total health spending of all states will exceed 100 per cent of their tax revenues, excluding the GST, by around 2045-46 - and possibly earlier in some states.

The NSW treasury has estimated that spending on health will almost double as a share of the NSW total Budget - from 30 per cent today to around 55 per cent in 2032-33.

These are challenging statistics, but it is important the nation becomes familiar with them, because we must do something about them.

Without reform - States ability to provide the services they currently provide will be significantly strained.

That is why 2010 must be and will be a year of major health reform.

Prime Minister Address to Australia Day reception, Sydney - 24 January 2010

The one success of Stephen Duckett's Victorian

Case-Mix Funding model is that it has reduced the episodic cost of treating patients in public hospitals. Basically the way it works is that for patients being admitted to hospital with a specific condition (or similar groups of conditions, or similar operations) they receive a set payment which is predetermined. In order to allow for variations in the cost of treating those conditions throughout the state or between hospitals, or the State Government's desire for each hospital to provide various types of services, a complex series of calculations are applied to the actual amount that a hospital can receive. Effectively, hospitals are given a target of patients to treat or procedures to perform. If a hospital goes over that target either on a patient-by-patient basis or over a financial quarter then there is no further funding - they lose money.

In order to determine the appropriate payment, an

audit is performed to estimate the costs involved with treating a standard patient in each hospital. This is compared to hospitals statewide and a statistical target is generated. Year upon year these figures are revised with more data, and hospitals try to make a little extra profit by beating their previous year's performance, until you get a "steady state efficient price" which is the price at which a hospital (the cheapest hospital) can treat a patient, most likely by cutting corners and taking risks - i.e. the price at which it starts to become unsafe to treat that patient.

As I intimated earlier - this is all about meeting budgetary targets, not about providing quality care. Doctors and nurses at the coalface are generally divorced from the cost of treating patients. Generally we like it that way as I don't feel guilty doing an ERCP on an 89 year old woman who will die in the next six months of a cholangiocarcinoma even if I save her life today. From a budgetary perspective the hospital would much prefer that I operated on a 20 year old man with early appendicitis than put the ERCP stent in, because it costs less to treat the appendix than the stent, but I have the luxury of not giving a shit, and therefore I am responsible for blowing out the health budget, as Kevin Rudd says.

There are perverse outcomes to this system (or "innovative solutions" depending which side of the fence you sit on). For example, the fewer days a patient is in hospital the more money a hospital gets for a certain condition. If you have shaved all the waste out of your hospital and are operating on maximum efficiency, the only way to get more money is to kick a patient out before they are ready. In order to combat this less money is paid if a patient "bounces", or is re-admitted for the same condition within 30 days. Therefore nobody comes in with the same condition within 30 days. They always have something unrelated to their last admission.

Furthermore, the more complications a patient experiences the more money a hospital gets. I remember my first day in a Victorian hospital included an orientation to

"DRGs" or Diagnosis-related groups and "coding". I never realised that if a patient has an episode of dysuria and an equivocal dipstick they can be coded as having a postoperative UTI and therefore the casemix payment jumps 50%. Similarly, everyone has hyperkalaemia or hypernatraemia at some stage, or pulmonary atelectasis, or a wound infection (even if no antibiotics are required), or acute urinary retention (averted at the last minute by the threat of an urinary catheter).

And as Stephen Duckett also pointed out:

Mr Rudd's promise to provide 60 per cent of hospital funding also risked generating a rise in unnecessary hospital procedures.

The fixed cost of running a public hospital accounted for about 50 per cent, with the other half generated by surgery and treatment costs for individuals. "That will be an incentive to increase activity," he said.

The Age - March 5, 2010

Lastly, there is another downside to Case-Mix funding. In order for it to work, the funding body must define what procedures and conditions it will fund. If a patient suffers from something unusual that falls between the "coding cracks" or undergoes a procedure that is not listed in the manual, then they are unfunded, and the hospital must pay for that treatment out of general revenue at a complete loss. This discourages hospitals from treating patients with unclear illnesses (

House would never survive in a Case-Mix funded hospital if it weren't for the fact that he does so many unnecessary procedures), and also discourages them from performing or rolling out new procedures or techniques which may have clear clinical benefits but are not in the list of funded procedures, unless a way can be found to "fudge the figures".

Ultimately, the real reason for this reform is to roll out the cost-capping measures of the Case-Mix funding system nationally. It provides a means to control and limit recurrent expenditure on health care in public hospitals over the long term. All the other claimed "advantages" are merely spin. This is the only valuable, long term and lasting outcome of these reforms. No doubt they are necessary, but it is disingenuous to hide this from the Australian public by overpromoting the other aspects of this reform.

The Underlying Problem

I have long held the opinion that the cause of ballooning costs of health care in this country is not the ageing population, or the costs of new drugs or devices (though these things do obviously contribute). It is that as a society we are completely incapable of drawing a line and saying that "This is as healthy as you need to be. If you want more, then you pay for it." Both the UK NHS and New Zealand health systems have had to overtly ration health care. South Australia has basically banned varicose veins surgery from public hospitals. Currently we prioritise but we don't limit what we offer in public hostels.

I do not speak from the moral high ground. I am no more likely to deny a patient varicose veins surgery or repair of a small hernia as a renal physician deny someone dialysis or a panelbeater recommend doing nothing to an insured smash-up. Generally as doctors we can tell when a treatment is futile, or unnecessary but ultimately we are people, and just like our patients - if a treatment is funded, the risk is low, and it works, then why not use it?

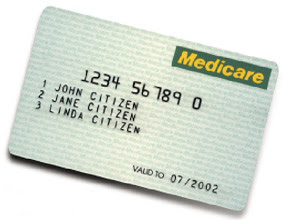

There is a precedent here which flies against the argument of those that say the Federal Government does not have the experience to roll out these reforms, and that precedent is Medicare. Medicare is effectively a case-mix system delivered on an outpatient basis. If you see a doctor, and you have a certain type of treatment (which correlates roughly to a certain condition) then the doctor receives a benchmark payment (75% of the Scheduled Fee). If the doctor's operating costs (+ profit) are greater than the reimbursement fee, then they charge you for the difference (the "Gap" fee). If the condition or treatment is not in the schedule, then the Federal Government does not pay and you get lumped with the whole cost.

Similar to the proposed efficient cost system, the Schedule fee is regularly revised (or some would say regularly ignored) to reflect the costs of providing each treatment. Sometimes the fee goes up, sometimes the fee goes down. Usually it goes down relative to CPI, and has (over the last 25 years) been a very effective way for successive Federal Governments to cap outpatient and primary care funding costs. Notice how the NHHRC said very little about primary care funding reform? It is because this reform is already in place, and the only thing that needs to happen is to turn the screws a little tighter as was recently attempted to cataract surgery.

I would predict that the nature of the Federal Government hospital reform funding rollout (Gee that is a mouthful) will closely reflect the way that private hospital cover is funded. Let us assume that the Medicare Schedule Fee for a Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy is the "efficient cost" of providing that service. The Federal Government currently agrees to pay doctors 80% of the "efficient cost" of that service. The remaining 20% comes from the patient's private health insurer. Any additional fees charged by the surgeon is paid for by the patient.

Similarly, private hospitals receive a payment for that patient's stay in hospital based on the patient's condition and their procedure, which is partly funded by state and federal governments but also by private health insurers. If those payments don't meet the hospitals costs then the patient is charged a further gap fee. All that Kevin Rudd and Nicola Roxon need to do is take that same system, insert "State Government" instead of "Private Health Insurer", apply it to public hospitals and voila - you have Public Hospital Medicare, with the added benefit that you can limit or reduce the "efficient cost" reimbursement as much as and whenever you like. If you don't want to pay for a procedure such as lap banding then you just refuse to add it to the list of funded procedures, and then it becomes the Local Board and the State Government's responsibility whether they want to pay for these unfunded procedures that the public is clamouring for access to… and the Blame Game continues.

We talk about a safety net but we are not brave enough to discuss how high or low the safety net should be positioned, or who we are really trying to catch. It is political suicide to say that some people need to suffer or die for the benefit of the rest of the community, even if that suffering is minor, or the death is inevitable. This reform is not about the "Blame Game", or restoring control to local or regional communities, or even improving the quality of our hospital system or population health.

It is about controlling the costs of health care in the long term, and it will work… for a little while, at least. But as I have pointed out before to my colleagues, Medicare (and these new Efficient Costs reforms) are basically the Australian version of public

Managed Care, and I hope that we do not end up at the end of a

Get Smart episode with Max lamenting: "If only Managed Care and Kevin Rudd's health reform had been used for good, not evil."

Links:- Rudd to tour hospitals on reform opinions - ABC Lateline July 27, 2009. Watch: Win Lo | Win Hi

- Health reform proposal receives mixed reactions - ABC Lateline July 27, 2009. Watch: Win Lo | Win Hi

- Roxon discusses health reform proposal - Lateline July 27, 2009. Watch: Win Lo | Win Hi

- Taxpayers may have to dig deep for reform - ABC Lateline July 28, 2009. Watch: Win Lo | Win Hi

- Dutton discusses health reform plans - ABC Lateline July 28, 2009. Watch: Win Lo | Win Hi

- Much more than bravery required - The Australian July 28, 2009

- Healing a sick system - The Australian July 28, 2009

- Ageing population to add to pressure - The Australian July 28, 2009

- Federal government gets casemix wrong - The Australian September 19, 2009

- Rudd's magic cure: more process - The Australian March 04, 2010

- Hands off our hospitals, Victoria tells Rudd - The Age March 4, 2010

- Health deal a bitter pill for Victoria - The Age March 5, 2010

- Hospitals reform: Rudd says states running 'scare campaign' - Daily Telegraph March 04, 2010

- Top bureaucrat casts doubt on hospital overhaul - The Age March 5, 2010

- Fears for primary healthcare - The Age March 5, 2010

- Health FAQs for the confused - The Australian March 05, 2010

- Rudd's cosmetic surgery - The Australian March 06, 2010

- New hospital roof a huge waste of money, say doctors - SMH March 6, 2010

- Voters know I'm right' - SMH March 6, 2010

- Health reform plan has rationalist fingerprints - SMH March 8, 2010

- Voters warm to Rudd's health plan - SMH March 8, 2010

- Health reform causes local concern - Singleton Argus March 09, 2010

- Show us the money, Victoria tells Rudd - The Age March 9, 2010

- To improve rural health, we need to move beyond the hospital focus - Crikey.com.au March 9, 2010

- Issues and challenges facing rural hospitals - David Wilkinson, Australian Health Review 2002, 95-105,25(5)

- Managed care: Implications of managed care for health systems, clinicians, and patients - Fairfield et al., BMJ 1997;314:1895 (28 June)

- Casemix: moving forward Special Supplement - MJA 1998

- Casemix: moving forward. The surgeon and casemix - John A L Hart and David Wallace, MJA 1998; 169: S51-S52

- About Casemix - Victorian Department of Health Website