Since the 4 Corners "At Their Mercy" episode this week, there has been some discussion about bullying over at PagingDr Forums, a great source of medical chat for those who are interested. Occasionally I go on a bit of a rant there, and obviously this issue has riled me up somewhat. Interestingly the 4 Corners episode was preceded by a very powerful and relevant episode of Australian Story on Retired Lieutenant-General David Morrison.

Since the 4 Corners "At Their Mercy" episode this week, there has been some discussion about bullying over at PagingDr Forums, a great source of medical chat for those who are interested. Occasionally I go on a bit of a rant there, and obviously this issue has riled me up somewhat. Interestingly the 4 Corners episode was preceded by a very powerful and relevant episode of Australian Story on Retired Lieutenant-General David Morrison.My last post was a rather personal piece, with relevant identifying features altered. It was about my experiences as a bully, but I have similarly experienced it differently as a victim. I have received some feedback that it does not help the cause of eliminating harassment and bullying from the workplace. I respectfully disagree, since I think that identifying and rehabilitating the bully is just as important as identifying and helping the victim. I also believe that there is a complex personal interplay in these situations which deserve more than a simple "I'm right. You're wrong" approach. That is a recipe for sudden, knee-jerk changes that can cause far more damage to a system than the benefits it may bring.

I can imagine the objections now, that medical bullies are heinous individuals that deserve to be stripped of their qualifications, their right to care for patients and to teach, and that they should be publicly named and shamed, or even executed. If you found out today that the surgeon who saved your life was a bully is that seriously what you would want to happen to them?

Also the other argument that is made is that the destruction of any career or the loss of life from suicide is tragic and that even if that happens once it is once too many, let alone four times in the space of a few months. Well that is absolutely true, and I agree completely, but we also accept that there is a road toll for the benefit of being able to zoom at speed around the country. We accept that there is a terrorist risk for all of the freedoms that we enjoy. Callous as it may sound, why do we now not accept that some people will not make it through training and might even be harmed in order for the general public to enjoy quality healthcare from highly-trained experts?

The question is how do we go about preventing those preventable incidents? What cost are we willing to bear in the pursuit of preventing them? These are hard questions, and they are questions that we as a society fail to answer, in the same way that we all want the best healthcare using the most expensive drugs and technology, but we also don't want to to pay greater taxes to cover the cost (currently ~9% of GDP).

This question was posed by an aspiring medical student over at PagingDr Forums:

I'd be interested to know how much infrastructure there is to teach doctor's working through the ranks leadership, mentorship and people managements skills... or even teaching skills? (Beyond observing those around them?). I realise doctor's are time poor but I wonder if formal development of these skill would go some way to improve things.

The Royal Australasian College of Surgeons runs training courses in professional and non-technical skills which encompass these areas of leadership, team communication and teaching.

- Non-Technical Skills for Surgeons

- Safer Australian Surgical Teamwork

- Supervisor Training Courses (SAT-SET)

- Keeping Trainees on Track (KTOT - to help struggling trainees)

- Training in Professional Skills (TIPS)

Some might argue that these should be taught earlier. Several other Colleges run similar programs.

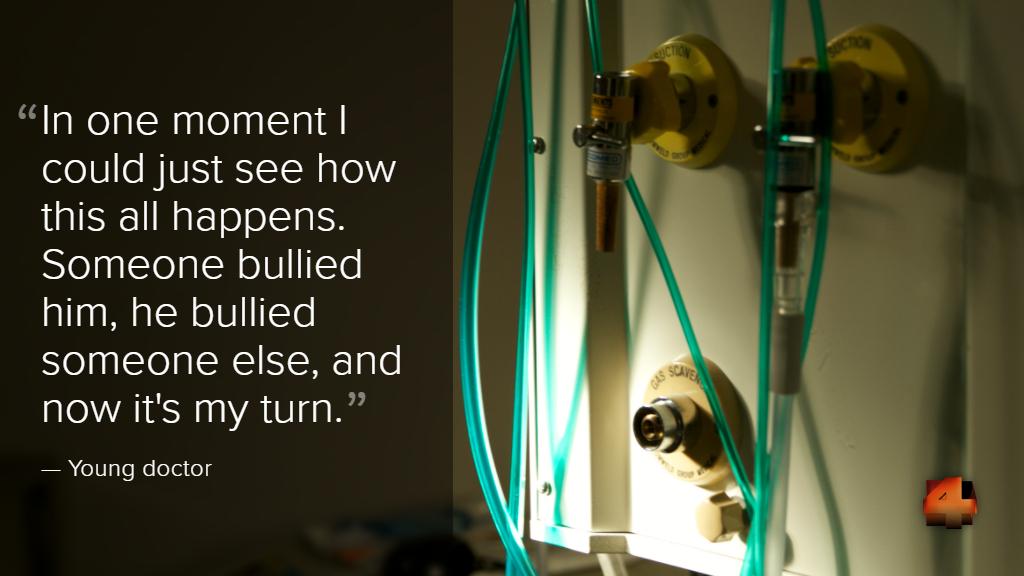

Another comment was from a doctor:

An issue that came up was question/answer method of teaching, and that this was bullying. I must admit I do this all the time and never felt like I was bullying anyone. Are medical students saying that ANY questioning is making them upset or is it just contextual, ie. Don't ask me in front of patients/other people?

Speaking for surgery, the Q&A type teaching mirrors the format of the final surgical exit examinations. You are in a closed room with two examiners who basically ask you questions until either they run out of time or you give up (for more information see here). Even if you answer all their questions they think of more until the bell rings. It is not practical to simulate that scenario in private on a regular basis during a working job, so the scenario is simulated at the bedside, at the operating table, or in unit/department meetings. The questioning is not intended to be malicious or threatening, but they are intended to be challenging, to tease out lines of logical thought or consideration, to highlight areas of deficiency and to promote motivation to self-study.

Unfortunately generations of doctors have been brought up with this myth (perpetuated in the media along with lots of other bad work practices because, heck, it's entertaining) that the questioning (or "pimping" which I think is a terrible term) should be used as a chance to mock trainees on their errors, to get them to "harden the F(*#@ up" and that it is most effective if they are pushed to the brink. It is also easy to forget that it is a public forum in front of other co-workers and not a private one like the exams. Lastly if there is a power imbalance then the questioning/teaching process is an opportunity to reinforce that, which sadly some seniors find irresistible. This practice has become so much a part of medical folklore that it is seen as a bit of a joke.

As for modern education theory that recommends that confronting trainees with their errors is wrong, and should be done in a safe, private, comfortable teaching environment after you have assembled a mountain of data about their errors and prepared a comprehensive performance management plan... well you can imagine the challenges of implementing that in a busy, service-oriented workplace.

The sexual component of the 4 Corners episode is what really kicked everything off, with Gay McMullin's rather inappropriate and deplorable comment that "What I tell my trainees is that, if you are approached for sex, probably the safest thing to do in terms of your career is to comply with the request". RACS has proactively worked to address bullying and harassment for many years, but the public seems to care more when it is sexual harassment, not just regular run-of-the-mill workplace bullying. This is very unfortunate because workplace bullying and harassment is a form of disruptive interpersonal conflict that is made possible by a power imbalance, and exacerbated by chronic and short-term stressors that develop amongst both the harasser and the harassee.

Remember that most definitions of bullying or harassment (and most certainly sexual harassment) is one that is based primarily on whether the harassee has taken offense or feels threatened. The intent of the harasser may not be relevant and harassment can be unintentional (see this Parliamentary document Section 1.55 "Intentional versus Unintentional Bullying"). Therefore factors that increase the harasser's aggressiveness and factors that increase the harassee's sensitivity will logically play into its manifestation. (I am trying to be polite here).

Sexual harassment is however seen as something that arises because of an innate "evil" within the harasser or workplace which is part of their nature and cannot be remediated. This is not a constructive way to view things. It is effectively shaming hard-working supervisors and teachers who have made a terrible mistake without offering them any form of salvation.

I think what is more relevant is the concept that there is occasional harassment that occurs in settings of heightened workplace stress (whether contrived or not) and there is harassment that occurs as a deliberate and repeated pattern of sociopathic behaviour. Regardless of whether there is a sexual component these are two very different scenarios which require two very different approaches. The former is a combined human factors and systems issue ("culture change" or changing the structure and methods of hospitals/teaching - realising of course that this could be very expensive both in terms of financial cost and time cost to surgical training and patient care systems) and the second requires identifying and rehabilitating the individuals involved (this may also involve punishment and/or compensation).

Ultimately the cases described in 4 Corners were tragic, but hopefully they represent a tiny number of the daily surgeon-trainee interactions throughout Australia and New Zealand. For those that are proven, they should not have happened. For those that are just allegations, they deserve to have their investigations completed without intererence. For the rest of us, it is a salient lesson in what not to do. More importantly it highlights what we should speak out about because as Ret Chief of Army Lt-Gen David Morrison said "The standard you walk past, is the standard you accept."